Greetings Loved Ones! Liu Is The Name, And Views Are My Game.

It’s funny how, sometimes, it’s the most obvious aspects of our personalities that have to be pointed out. For some of us, this anomaly comes in the form of discovering strange little quirks, like arranging the food on our plate in a certain way, that we never knew we had. For me, it came in the realization that I absolutely adore strange stories. Now when I say “strange stories,” I’m referring to imaginative books or films with slow-paced, intricate plots, and vivid, dream-like images. Such stories often take unexpected turns into the realm of the surreal or fantastic, usually with little to no explanations why. Books that might fall into this category include The Wind-Up Bird Chronicles by Haruki Murakami, One Hundred years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez, and The Trial by Franz Kafka. Films that fit this classification include Nicolas Winding Refn’s Valhalla Rising, Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, and just about every picture produced by David Lynch.

Anyway, I came to the realization that I have an almost insatiable appetite for the absurd while waiting for Takashi Miike’s Gozu to arrive in the mail. Gozu, which literally means “Cow’s Head,” is a 2003 cult film from one of Japan’s most infamous directors. Nearly every review I’d read described it as, hands down, the absolute weirdest, most surreal piece of work put to the screen. This, of course, caught my attention, and so naturally I placed it at the top of my Netflix queue. It was while I was waiting for that lovely red envelope to appear in my mailbox that I realized something. This was, without question, the most excited I’d been to see a movie in a long time. This got me thinking. Did I like weird movies more than regular ones? No, I told myself, of course not. It was not the strangeness of the picture that had attracted my interest. It was the fact that the movie was directed by Takashi Miike, the man who brought the world such masterpieces as 13 Assassins and Hara Kiri: The Death of a Samurai. Still, as time passed, I started to notice certain details that flat out contradicted my denials. Some of my absolute favorite movies–The Big Lebowski, Life of Pi, and The Triplets of Belleville–are pretty darn weird. In addition, four of the movies that I’d reviewed on my blog–Dead Man, Oldboy, Valhalla Rising, and The Crying Game–were extremely strange. Faced with all this cold, hard evidence, I decided there was no point in lying to myself any longer. I loved weird movies, and that was why I ordered Gozu. Having finally accepted this part of myself, I was able to view the picture with no inhibitions.

Now some of you might be thinking, “Alright, so you had no inhibitions while watching it, but did you actually like it? Was it any good?” Yes and yes. In addition to being highly entertaining, Gozu was just as weird as everyone described, if not more so. It had unique, effective cinematography, extremely creative characters, and an eerie soundtrack that leant itself well to the story. Watching it was like seeing a René Magritte painting get turned into film. Yet despite the fact that I thoroughly enjoyed this picture, I wouldn’t recommend it to most people. It’s over two hours long, meandering in some places, and flat out disgusting in others. Also, I’ve learned over time that most people don’t share my love of foreign films so, for all you out there who hate having to read subtitles, this movie’s definitely not for you. But, all weaknesses aside, Gozu is still a highly unique work of art that should garner more attention from analytical movie-goers. That’s actually what I intend to convince people of in today’s analysis. However, before I can do that, I feel like I should explain a few details to those readers who are unfamiliar with the director and genre.

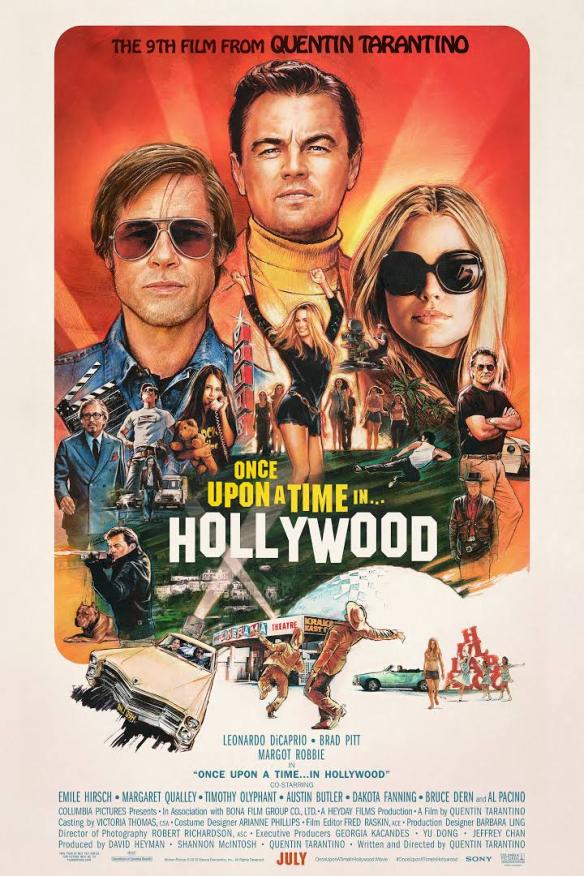

First of all, the man who made this movie, Takashi Miike, is someone who recently made his way to the top of my favorite filmmakers list. You’ve probably never heard of him but, with more than 50 pictures to his name, he is one of contemporary Japan’s most prolific directors. He is also one of the most controversial. Miike has often been described as the Japanese equivalent to Quentin Tarantino. I suppose it’s a valid comparison. Both directors have garnered international notoriety for depicting shocking scenes of extreme violence and sexual perversion. In addition to this, both men are famous for their black sense of humor and for focusing on the activities of criminals and minority peoples in their films. Beyond these few features, however, one simply cannot compare the two. See, where Tarantino is sort of a one trick pony, only making strange, ultra-violent movies, Miike has expanded his repertoire into a wide variety of genres, including period pieces, family comedies, musicals, dramas, and horror. I was actually introduced to him through 13 Assassins, one of his more innocuous, mainstream movies, and have yet to see his most controversial projects–Ichi the Killer and Visitor Q.

What I like about Miike is that, while he’s as showy and over the top as directors like Tarantino and Baz Luhrman, he’s also very subtle and profound. Many of his films, such as the horror classic Audition and the crime drama Ley Lines, deal with difficult and controversial issues, including the sexism and xenophobia that are all too present in contemporary Japanese society. That’s part of the reason why I was interested when I heard about Gozu. I wanted to see what new message Miike was trying to get across. Everyone had told me that Gozu was strange, and I figured he’d made it that way deliberately in order to get some political or social agenda through to the audience. Then again, it’s equally likely that he’d made a weird movie simply because he wanted to make one. There’s a whole genre of films out there that exist simply to poke fun at the notion that stories have to have a meaning. Almost none of the pictures that the Coen Brothers do make any sense, and the black comedy Rubber even advertised itself as an “homage to the element of nonsense that exists in every story.” But, I’ve kept you all waiting long enough. Let’s begin today’s analysis of the beautifully bizarre breakthrough that is Gozu.

Concerning plot; If you thought movies like Mementos, Mullholland Drive or Donnie Darko were confusing, you probably aren’t prepared for the picture I’m about to describe to you. What it is, in essence, is the story of a low level criminal trying to find the body of a man he accidentally killed, but in reality, it’s so much more than that.

The film starts in a restaurant where a group of Yakuza (Japanese mobsters) have gathered for a meeting. One of them, a man named Ozaki, appears to have lost his grip on reality. He takes his boss aside and directs his attention to a young couple standing outside the restaurant. The two have this tiny little chihuahua type dog with them, and Ozaki insists that it is, in fact, a creature that has been trained specifically to kill Yakuza “made men.” He then proceeds to go outside and smash the poor little thing against every conceivable surface until, at last, there’s nothing left except a bloody mass of fur.

Recognizing that Ozaki has completely lost his marbles, the boss orders him killed. He tells Minami, a Yakuza underling, to take Ozaki to a dump in Nagoya to be disposed of. However, before they can get there, Minami crashes his car. This causes Ozaki to bang his head and, apparently, go cold and stiff. While obviously shocked at having just killed someone, Minami is nevertheless relieved that Ozaki went out in a relatively quick and painless manner. Deciding that he should tell his boss, he pulls over to use a pay phone. When he turns around, however, he discovers that Ozaki, who was dead only moments ago, has vanished. Terrified and confused, Minami searches all over the city for signs of the missing corpse, but to no avail. He eventually stumbles across the dump where he was supposed to bring Ozaki, and asks the gangsters there for help. They agree, and offer to put him in an inn for the night.

The inn they end up choosing is run by an elderly brother and sister, who are just about the creepiest, most socially awkward people imaginable. Don’t believe me? Well then, why don’t I show you what we’re dealing with here. While Minami is taking a bath, the sister comes in and offers him some breast milk. Now remember, this woman is at least sixty years old, so its anyone’s guess how she still manages to lactate. When Minami refuses her offer, screaming, “No! I don’t want any milk!” she sighs and says, “A lot of our customers have been saying that lately,” before getting up and leaving.

The next morning, Minami gets the hell out of there and goes to a diner run by three transvestites. Why he would find this establishment any less weird than the place he just came from beats me but, to be honest, you learn to stop questioning this movie after a while. Anyway, while he’s there, he meets a person who claims to have seen Ozaki. He follows their directions, which take him all over Nagoya before bringing him back to the inn from earlier. Apparently, a man matching Ozaki’s description rented a room the night before, and the creepy brother and sister just neglected to tell him. Minami asks to stay in Ozaki’s room, and the innkeepers agree. That night, a minotaur (yes folks, I did just say minotaur) comes to visit Minami and offers him some red beans and rice. No explanation is ever given as to why this vignette was included or what it means but, like I said, you learn to stop questioning things after a while. The next morning, Minami awakens to find a note by his futon. This letter, apparently written by Ozaki, instructs him to go to the dump where the boss ordered him to dispose of the corpse. When he gets there, however, its only to learn that Ozaki’s body was pressed the day before. The mobsters there even show him the flattened corpse, which they keep hanging on a coat wrack wrapped in plastic like in a dry cleaners. This leaves Minami crushed (no pun intended) and confused.

However, before he gets a chance to ask the time of day, he gets hit with another curve ball–a rather curvaceous and attractive curve ball played by gravure idol Kimiko Yoshino. A mysterious woman appears in the back seat of his car and claims to be Ozaki. When he scoffs at her odd assertion, she proves to him that she is telling the truth by repeating, word for word, a dialogue that the two of them had earlier in the film. Confused at this turn of events, but deciding to go along with it, Minami takes the female Ozaki with him back to Tokyo. However, when he presents her to the other mobsters, his intention being to explain that the bombshell he has with him is, in fact, their brother in crime, his boss becomes besotted with her and doesn’t give minami the chance to speak. He chats her up a bit and then spirits her back to his apartment for some perverted sex. How do I know that its perverted sex? Well, in order to get a hard on, he has to shove a metal spoon up his ass. Yes. I did just say that. If you value your sanity, you won’t feel the need to read that sentence again. Anyway, Minami realizes that his boss is really going to do the nasty to Ozaki, so he decides to save her/him in one of the most over-the-top and, in my opinion, unintentionally funny manners possible–by swinging through the window on a rope like Tarzan. He kills his boss by touching the tip of the spoon with a caddle prod, don’t ask me where he got one of those, and takes Ozaki back to his place. There, the two have sex, which for some reason causes the woman to give birth to the original Ozaki. Now, when I say, “give birth,” I don’t mean to a baby. I mean the full-grown, fully-clothed man from earlier in the film comes out. And that’s not even the weirdest part. After the birth scene, we cut to a shot of the Tokyo skyline. Minami explains in a voice-over how, “we put the girl in the tub and she went right back to normal.” We then get a shot of the female Ozaki, alarmingly calm and composed considering what just happened, sitting in a bubble bath brushing her teeth. And if you think that’s odd, wait till you hear this. The scene right after this shows Minami, Ozaki and the female Ozaki walking arm in arm down the street. And you know what happens next? Nothing! The movie just ends there.

Now if, at this point, you’re thinking something along the lines of, “what the fuck?” don’t worry, that was my initial reaction too. As you can see, Gozu is a really, really, really weird film, arguably the weirdest that I’ve ever seen. Now to some people, the weirdness of this story exists solely to confuse and entertain the audience, and while I can see the validity of this argument, I’m not sure I agree with it. Yes, the twists are highly amusing, but I do think that Miike had something larger in mind when he added them. What that something was, I don’t know, but I do have a theory.

To me, Gozu is a cinematic exploration of sexuality confusion, with elements of Greek mythology thrown in. How, you might ask, could I possibly come up with such an assertion? Well, in terms of it being mythological, the film manages to artfully weave several aspects of the old legends into the plot. Like Perseus, Minami encounters a minotaur on his journey, and like the blind prophet, Tiresias, Ozaki undergoes several transformations, changing from a man to a woman to a man again.

As for the “sexuality confuseon” claim, the clues are everywhere, if not altogether obvious. Sexual imagery is present in almost every frame, particularly phallic symbols. Numerous characters, including Ozaki and the creepy female inn-keeper, comment on the size of Minami’s penis. When the gangsters at the dump show Minami Ozaki’s flattened corpse, Minami’s gaze is shown lingering on Ozaki’s junk. What all this indicates to me is that Minami is actually gay, most likely for Ozaki, but not comfortable enough with the fact to share it with anyone. This constant pressure to hide his secret, coupled with a sense of guilt at having to kill a man he’s attracted to, has caused Minami so much stress that he’s starting to hallucinate. How else might one explain the bat-shit insanity unfolding all about him? Now I realize that this whole idea might sound totally bogus to some of you but, if you think about it, it makes sense. Minami appears to have very strong feelings for Ozaki, and ones that go beyond simple admiration. When Minami receives the order to kill Ozaki, he becomes incredibly nervous and antsy–more so than one might feel if they were simply unfamiliar with killling. Then, when Ozaki disappears, Minami becomes frantic and spends the rest of the film trying to find him. When he does so, he doesn’t kill him, as he’s been ordered to do. Rather, he welcomes him with relief, and does everything in his power to protect him, even going so far as to kill his boss. The final bit of proof can be found in the sex scene between Minami and the female Ozaki. Minami knows that this woman is actually a man, but decides to have sex with her anyway. Why? Because he, a closeted gay man, has found an outlet through which to satisfy his needs, and in a manner that, on the surface, conforms with societies standards of acceptable behavior. The birth scene that follows symbolizes Minami’s full acceptance of his sexuality. He, like the male Ozaki, is coming out into the open.

So what, in the end, does all this sexual and mythological nonsense add up to? What’s the movie trying to get across? Well, in my opinion, it’s Takashi Miike’s method of subtly criticizing homophobia and society’s narrow perceptions of gender. That’s certainly the most provable reading to have. All the right images, motifs and plot elements are at your disposal but, truth be told, its equally likely that this movie has no meaning whatsoever. And in a strange way, that’s what so great about it. In addition to being an extremely enjoyable sojourn into insanity, Gozu is just specific enough in its content to be seen as more than simple psychedelic entertainment. It dares you to believe that there’s something more to it, that there’s a hidden message tucked between the wide shots. And at the same time, its not annoyingly didactic either. You don’t come out of it choking on a processed moral like you might with Wall Street or Blood Diamond. Rather, your left with a sense of wonder and confusion. “That was really weird,” you might say to yourself. “And you know what, I think it was trying to tell me something.”

And that, dear friends, is why Takashi Miike’s Gozu should be at the top of more movie-goers “must see” lists. Thank you all so much for staying with me for this long. This is Nathan Liu, signing off.